The Shadow of Meaning Was Beautiful

Sung-weon Kang

- Autobiographical Cultural Theory

- The Truth of Misunderstanding

The more I live, the more I think, “I have misunderstood everything.” Oftentimes I misunderstand my own body and self. Even so, life is administered under the title head of document and theory.

The essentials of the situation come together in a wheel of reality that rolls along according to the particular time and space of an object or a topography, spinning out a truth and a sincerity that are more real than the real, and interlinking most everything with errors and misunderstandings that, on rare occasions, lead one to reality. This history, defined as the real, seems to begin here. To see, however, or not to see the real in a reality based on error and misunderstanding is unimportant. Or rather, it seems unimportant. In any case, we live by thinking that we feel and decide.

Some believe that if they define their quality of feeling and knowledge, the result is conflict or inequality. Knowledge is always valuable when it leads one to discover the new, or it elevates what one appropriates to the level of intellect until now.

My artistic education has been based on the history and theories of Western art. It has given me no concept of traditional art and no historical content. When I think about it, its stunning. The Korean artists that I knew during my studies were Kim Hong-do (1745-1816?) and Shin Yun-bok (1758-?). I learned about them not from any course but from illustrated calendars.

The words “to know” are ambiguous and tiresome. The things we know about Western art are like iconic knowledge obtained through negotiation.

As soon as they function, icons take charge of reality. Icons replace reality and move us. In the shadow of signs and their values that icons give flower to, genius blooms. Whatever gives hope and determines our interests, acts, and goals comes not from knowledge about Picasso or about the true artist in Picasso but, it seems, from the concepts that gravitate around the painting genius in Picasso.

The concept of Picasso, not to be confused with the real Picasso, elevates contemporary art in our hearts, much like how the differences in our ideas of freedom, love, peace, and real experience, or else the simulation of meaning based on these differences, gives eternal life to such concepts.

Knowledge of Western art creates in its own way the concept of (Western) art and becomes a personal belief system in Western art. This knowledge becomes a tendency more than a reality, and is like intellectuals who function as icons and have an idea of “Western art” that they communicate to our hearts. Knowledge, half of which is composed of every color, opens our eyes to a sight that can be broken down into differences in quality and manner, both attracting our perception and offering more satisfying results than the real.

Sometimes I think that the history of Western art in Korea is more Western than the history of Western art is in the West. Each people can see its “Western” history of art differently from all others. Sometimes one wonders if Western art history really existed as art history. Perhaps this kind of knowledge has been necessary for globalization. For although one must know, one must know in a superficial fashion, lest understanding and synthesis become difficult. Knowledge is a sham, domination is an unimpeachable reality. The sham is, in a sense, more real than knowledge.

It is this kind of thought that clogs my brain.

To me, traditional Korean art seems stranger and more difficult than Western art. Confucius makes un more uncomfortable than Aristotle.

In ancient Greece, Plato had already stated that there is a world where falsehood is truer than truth. With the love of knowledge we discover the world of ideas. Which of the following statements is truer? One: In an existential sense, purity is the highest value. Two: Truth is the highest value.

Yet “truth” can only be “true” through the existence of the icon. Semiotics is in reality no big deal. All it does is confirm a given experience. On the other hand, the icon functions as the absolute real in truth and ideas. It is no longer a question of what the true essence of art history is. [1]

Truth is legion. The weight and the quality of truth are equal. We are equal because we are sincere, not because we know truth.

- A Drifting Island

South Korea in the nineteen-nineties succeeded in rebuilding old alliances. At the end of the twentieth century, Korea had no diplomatic relations with the socialist countries of China and Russia. On the other hand, Korea was on friendly terms with America, some European nations, and Japan, which had colonized the peninsula.

North Korea shares borders with China and Russia. Any land route from South Korea to China or Russia must pass through North Korea. Until the nineteen-eighties, Korea, a peninsula, was more like an island surrounded on three sides by the sea. Today, it is geographically but not politically possible for a South Korean to cross the Demilitarized Zone and to reach North Korea by land and, beyond that, to cross both the Iron and the Bamboo Curtains separating North Korea from Russia and China. In these circumstances, the closest country to Korea has been Japan. On a world map, America is far away from Korea, beyond the Japanese archipelago and across the Pacific Ocean. On August 15, 1945, Korea, after 36 years of Japanese rule, was finally liberated by America and its allies. Korean liberation also meant severed diplomatic ties with Japan, which South Korea and Japan only restored in the nineteen-sixties.

After the liberation and during the Cold War, South Korea also established new diplomatic relations with other neighboring countries. The civil war, which lasted three years, from 1950 to 1953, divided Korea into two bitter enemy countries.

Today, with the end of the Cold War, South Korea has renewed a long history of diplomatic relations with China and Russia. Neither of these three Northeast Asian countries was able to be good neighbors during the period of “modernization.” Any product or idea from Russia and China’s modern, socialist cultures was forbidden in South Korea, and Japan’s slightly more familiar culture was presented by the Korean government to the public in a biased, manipulative way. Modern Japanese culture has always had a back-alley type of influence on South Korea. Even so, the rest of Japanese modern culture, which established itself in Korea during the occupation, from 1910 to 1945, has always had strong roots.

Today, Japan and China are already psychologically foreign and far away from Korea. Although it is true that in the past Chinese culture had a strong influence on Korean culture, today, it is American culture that has the strongest influence on Korea, while French and German culture exert lesser influences.

Since the nineties, and after a half century of closed borders, South Koreans are once again traveling freely to China and Russia. Of course, the historical conditions that now allow us to travel freely to China and Russia are out of our hands. Be that as it may, since the nineties, South Koreans have been living a period where, for the first time since modernization, we can rebuild, with a historical, subjective consciousness, relations with Northeast Asian countries.

In a sense, this South Korean reality seems to be heading toward a kind of reversal of modernism or a de-modernity. This direction is not, however, toward a de-modernity in and of itself, but toward the construction of a new societal perspective. Revealed in this way, this perspective on life has always exemplified the will of a people seeking to form an image of itself that transcends the modern.

- Grammar

- The Beginning of Meaning: Representations of Will Power and Changing Signs.

When we speak of “Korean painting, “[2] we often mean the traditional, literati-style painting made with black ink and some watercolor on Asian paper. A close analysis of this painting genre reveals that it has no particular content apart from its signification as a traditional art. However, today, just as the words “Western painting” evoke oil painting, “Oriental painting” probably evokes this traditional black ink and watercolor style.

The major movements in Western painting revolve primarily around works that present a desire for consciousness and a monumental character. In front of these works, the artist exists as an observer outside the object. Or else the sensibility of the artist imposes the world of the artwork.

Unlike Western painting, literati painting is the painting of will power.”[3] And although it represents will power, its creator is uninterested in its essence.[4] The literati painter’s priority is how will power and its representation culminate in the highest expression of culture. Yet the concept of culture in literati painting is the artist’s resolve toward the will of the public and, at the same time, his own inner resolve. [5]

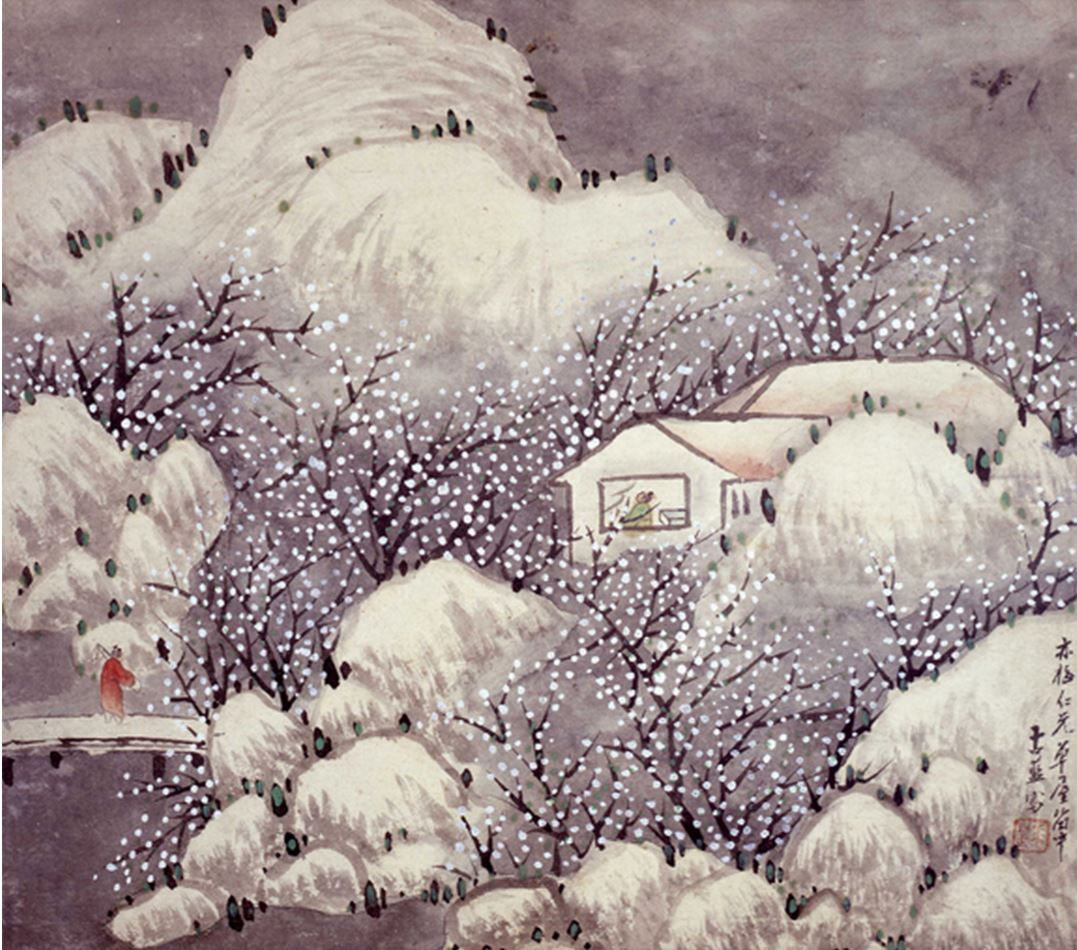

JeonKi’s Grass-Roofed Hut with Plum Blossom, Korean watercolor on paper, 32.4×36.1cm, 19th-centrury

The literati painter transforms will power into an aesthetic. An example of this is the landscape painting, where a mountain is not necessarily a mountain. The mountain is a representation of will power. Icons in literati painting also function as signifiers, but they abstain from communicating a real situation or the elaborate circumstantial description of Western painting. Literati painters paint to show their inner icons’ significations. They make no effort to communicate. They communicate content effectively. They communicate their own intention but change it into a form of will power.

Literati painting represents significations defined by cultural custom. [6]This is perhaps why it has no need for Western art techniques such as linear perspective or anatomically correct body renderings or a camera obscura.

Literati painting is the aesthetic meeting of competing relationships between the public norms and the cultural harmony and disharmony of the artist’s will power. Here, the degree of a painting’s realism is unimportant. What is important is to paint what one intends to paint by bolstering one’s work with representational principles. For example, while literati painters paint symbols of constancy, they also know what an ultimately important position they must take to manifest a will power that approaches constancy not concretely but abstractly.

The ultimate position speaks only through figurative forms. The form guarantees the difference in quality among different content. Artists only particularize their own normative culture of seeing.

Although the culture of seeing is also a culture of interpretation and appreciation, it does not look at the object as such but as a cultural signification that transforms the object into a symbol. “The culture of seeing” looks at “meaning” through its own lens. Evaluation determines if the artist’s intention is literally realized.

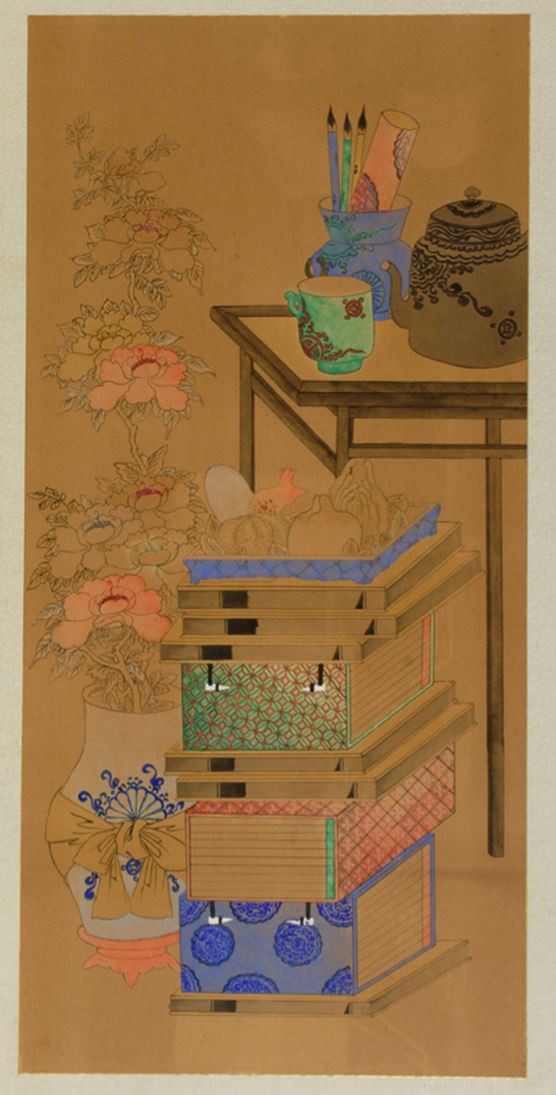

(left) Ch’aekkori painting, painting on silk, 96.4×45.8cm, Joseon period

(right) Sansindo, painting on silk, 109.5x81cm, Joseon period

Whether it is Western or Oriental, traditional art functions as a kind of visual language. In the past, when reading and writing were for the cultured elite, traditional art was a common language for everyone, regardless of social class. In reality, faced with the public will, one has to conduct oneself correctly or, as in folk painting, to remain silent except to wish someone well or for harmony for a couple or for double happiness or longevity.

Traditional Oriental art is imbued with the public values of traditional norms. Traditional art was the place where the artist targeted and, consequently, cultivated the public will.

What one has in one’s heart and mind is the will to act. To have the act is to establish will power. Artists direct their attention toward places of public communication. Beyond this, the communication of their vision can only become the ideal direction. Or else they and their will power, when thwarted, can only take exile in the countryside or sequester themselves, while dreaming of contentment in poverty and delight in the Taoist Way.

Contentment in poverty and delight in the Taoist Way is the ideal public world of literati painting. It is an especially meaningful value for our art culture, one that has been built from a concept. This is why the culture of seeing in Korea has been able to develop the culture of evaluating quality. The culture of art in Korea, while cherishing the ability to look, has formed a cultural concept of seeing the invisible. The essence of the culture of art in Korea has existed as an invisible aesthetic that embraces not the culture of visual creativity, but meaning in what is common in daily life. The culture of Korean art has been more a creation than a production.

- A New Cape of Meaning

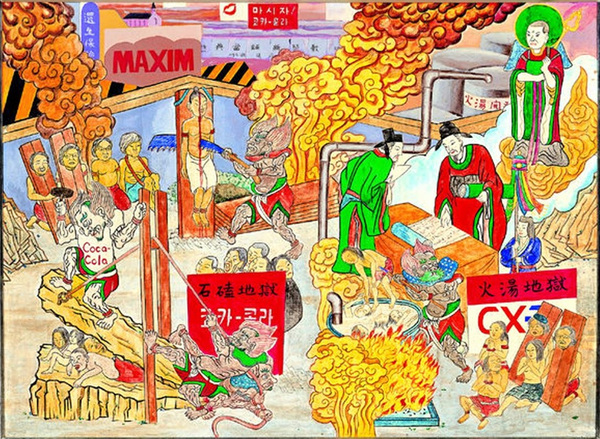

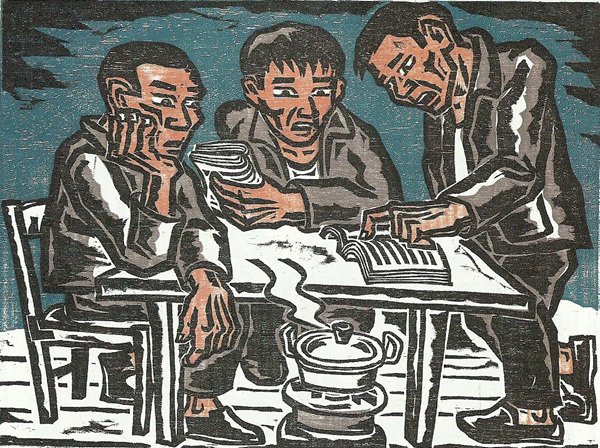

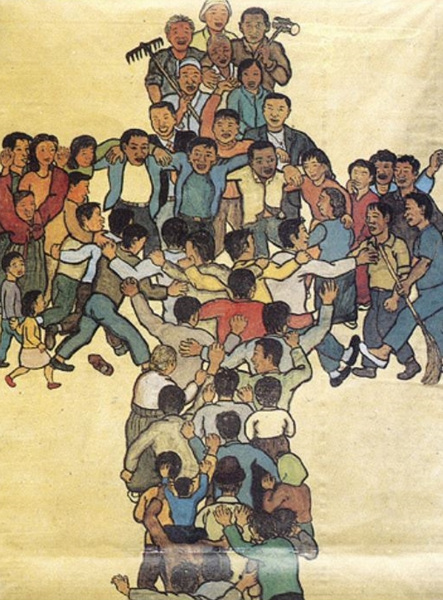

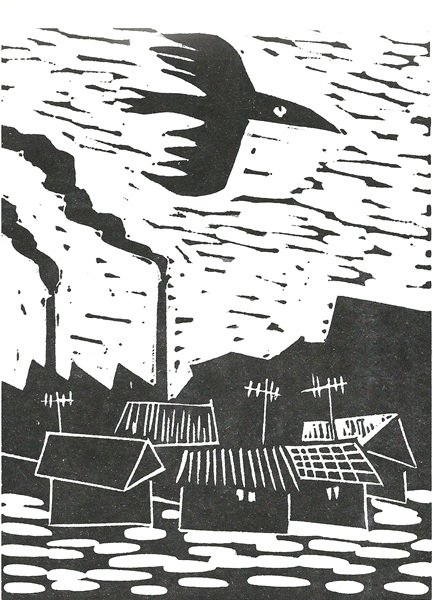

“Minjung” (Korean for “People’s”) art was an art movement whose goal was to ensure a Korean artistic language. This progressive art movement appeared in Korea in the nineteen-eighties, beginning with a critique of the derivative quality of Korean Modernism’s artistic language and ideology. The Minjung movement asserted that the artistic heritage of traditional life had become isolated from modernization and tried to establish an art for the people in Korean culture. It was especially clear that a declaration on the reality of art should be established by the artist as intellectual.[7]

Jaehong Kim, Saeya Saeya Parang Saeya, oil on canvas, 480*190cm,1994

Yoon Oh, Marketing1_Hell, mixed media on canva, 131*162cm,1980

Beomjin Cho, My study, woodcut, 35*26.5cm,1988

Kyeongtae Choi, A Winter Morning_the people waiting Sunday, oil on canvas, 193*130 cm,1992

(left) Bongjoon Kim, the cross for emancipation, 350*500cm, acrylic(missing), 1983

(right) Junkwon Kim, a thistle 2, Woodcut, 53*35.5cm,1991

(left) Jinho Cho, at Songgwang temple, woodcut, 15*20cm,1983

(right) Jae whan Ju, Mondrian Hotel, copied colour drawing, 202*152cm, 1980

By the beginning of the nineties, Minjung art had remained an institution of the eighties, incapable of responding, in form and in content, to the changing demands of the times. Because it was now a public fixture, Minjung realized a people’s cultural basis for contemporary Korean art history. It was not able, however, to succeed on the art market.

Minjung art was made by progressive artist-intellectuals in Korea. Since the nineties, however, these artists have ceased to express a concrete aesthetic vision that, in a historical sense, might serve as an artistic vanguard for the Korean people, in a nascent democratic society. They are now creating a people’s art in which the real has disappeared. The nineties brought muddled artistic values, both Modernist and Minjung, to the Korean cultural terrain. New artistic values and practices were nowhere to be found.

Since the end of the Cold War, Koreans have been faced with a different culture and politics from the recent past. An interpretation of life before and during modernization and at the advent of today’s new reality and a vision ofa new life based on this interpretation have yet to be attempted, because we haveyet to find a central signifier in which the meaning of our true culture appears.

In Korea, although Modernism in the sixties and seventies was the official art, it met with little public enthusiasm.[8] Modernism, on the other hand, was commercially successful, but since it had inherited nothing of the people’s culture it left the public inddifferent toward both its concepts and emotions. The history of Western art in Korea had becomea sanctuary, with no basis in reality, for artists’ study of art since the Renaissance, a place where one infrequently saw Western artworks in the flesh.

A look at the past reveals that Minjung and Modernist art have always been profoundly linked to politics. However, viewed from the outside, Korean culture in the nineties appears to confront reality for the first time without having to deal with a military dictatorship or the Cold War. In reality, today we can finally hold a discourse on the cultural successes and failures of the left-wing and right-wing ideologies of the twenties century.

If today we are experiencing cultural confusion again, it is because of the postmodernist debates of the early nineties that were the most important discourses in the art world. The postmodernist ebate signaled the beginning of the end of Minjung art, and with it the problem of developinga successful people’s art movement disappeared from the scene. Minjung artists themselves lost their vision and became confused by the development of the postmodernist discourse.

Postmodernists consider their discourse a new aesthetic strategy. The heated debate around postmodernism has pushed aside other major aesthetic currents in Korea, including artists whose work has always been independent from Modernism and Minjung and certain Minjung artists who have been experimenting with an updated people’s art by borrowing art forms from traditional daily life.[9] Korean painting has yet to suggest a new vision, almost as though it has been caught completely off guard by the present situation. The postmodernist discourse in Korea has been received like a capitalistic vanguard out to propagandize for globalization.

The postmodernist discourse has thus become but a passing phenomenon. Now there are artists who want to resolve the problem again of “how to look at something.” The direction of their preoccupation is, in reality, very similar to that of Western painting, although artists, faced with a discourse on the endangered identity of contemporary Korean art or on the danger of international art, have no choice but to reexamine the beginnings of art.

Thanks to this situation, artists have been trying since the nineties to make a new start by reading and mastering our real culture. Now both Modernist and Minjung artists, although choosing subjects and materials with the creative methods and the ideologies of Western art, are looking at reality by means of the culture that they are experiencing and sharing.

Western artists see art as creative visual representation.

Traditional Korean artists see in art the larger meaning of being “a culture of seeing.” Korean traditional art sees cultural meaning in everyday experience. Meaning is created by one’s will to see the object. Korean cultural values demand a certain aesthetic in the relationship between quality and the yin and yang of meaning, where harmony is created in the relationship of the part to the whole, and where daily life and its relationships form an artistic culture.

In reality, many works in Korean mainstream modern and contemporary art history have borrowed their style, viewpoint, and subject from the artistic tendencies and thinking of Western art. The source of many of these paintings is the Western artistic discourse that has been for some time now theoretically and critically dominant, while the source of others is the obligation felt by artists to respond to the power or the zeitgeist of the times. Artworks from mainstream modern and contemporary art history seem only in appearance to be constant to the spirit and grammar of Western art. In reality, one might say that unconsciously they repeat creative attitudes of traditional art.

These works demonstrate the will power of artists who take on the grandiose discourse of Western art. In the end, their works express an art of will power in traditional artists.

This grandiose discourse is one way for the artist to treat popular subjects and materials while only sharing an awareness of the problem. The resulting art is imbued with the artist’s response to this discourse and will to observe it.

Of course some artists are not like this. They cannot become mainstream artists. For Korean artists, it is perhaps more natural to paint according to their will power and personal direction.

III. A Shaky Perspective

- Distortion

There is a concept that preoccupies Korean artists who ponder the modern heritage of traditional art and art worthy of Korea today: Korean aesthetic beauty.

Historical discussion on this concept is understood as a shortcut that, from its beginnings in the hands of Japanese aestheticians during the occupation to Korean art historians today, guarantees Korean artistic identity.

When it comes to the genius of Korean art and literature, in order for us to identify and conceptualize categories such as the identity of the Korean spirit, of Koreans, and of Korean culture, we must invoke the idea of Korean aesthetic beauty.

When I give it serious thought, I realize that the concept of Korean aesthetic beauty is very Korean. To discover the special beauty in the culture of a people is to confirm its cultural identity. If this is true, then Korean aesthetic beauty must be the lifeblood of the people through which the history of its culture runs in every direction. It must be at the conceptual level of values or be a concept for all people.

The problem until now, though, has been that the meaning and perception of Korean aesthetic beauty ignore this supposition. From this point of view, the conceptual difficulty of Korean aesthetic beauty reveals even more its concrete Koreanness.

Ko Yu-sup (1905-1944), the most important aesthetician in modern Korean art history, expressed the unique beauty of traditional Korean art in the concept “a craft of non-craft.”[10] The psychology of Korean aesthetic beauty provokes our awareness of the identity and spirit of the people from the sole point of view of beauty, by distinguishing between the values that produce traditional life and the beauty of the people’s culture, and the people’s awareness that culture becomes separated from life when values are isolated from cultural production and nostalgic activities.

(left) plum blossom and bamboo painting on White and Blue Porcelain, 12.4*7.3cm, The Joseon dynasty

(right) Punch’ong, decorated bowl, 9.4*16.4cm, 15th-16th century

(left)Hong-do Kim, Lunch, color on paper,27.0.*22.7cm,18th-19th century

(right)Yun-bok Shin, Jeojatgil, color on silk, 29.7*24.5cm,18th-19th century

Until now the concept of Korean aesthetic beauty has been too rigid for formal aesthetic categories. But since Korean aesthetic beauty represents the spirit and culture of the people, it must finally guarantee certain values and a worldview.

A history of art for the people is the last instance of certain meanings in the humanities, and is composed of a history of signifiers in relation to significations. The history of Korean art today, which includes both Western and Korean tendencies, is losing its connections to consciousness. It is no exaggeration to say that this is threatening the existence of the humanities in Korea.

The problem of understanding Korean aesthetic beauty proves that Korean humanities are built as a system of signs cut off from the aesthetic of the everyday and oblivious to real life problems. That each system of values in the different branches of the humanities is isolated from the others means that each one communicates only within its own system of significations. The concept of Korean aesthetic beauty dresses up the illusion of a meaningful body, like a phantom floating over the isolated branches of Korean humanities, and replaces the absence of a concept for the world and for values that could save meaning by understanding it.

- Good Eyes

Every culture is a culture of values, and every system of signs, including language, is a theory of values. Perception of reality, perhaps boring but still worth repeating, implies that the signifier of the signified is the sign that indicates a value.

The concept of Korean aesthetic beauty seeks to express the cultural identity of the people but does not reveal its values. It has so far revealed visual beauty from the outside. Artists, misunderstanding that Korean aesthetic beauty is the revelation of values in Korean culture, only bring out the particular visual beauty of Korea in their works.

Korean aesthetic beauty is a concept of values that the spirit of the people has developed, and an aesthetic concept in its representations. If an artist creates with the idea that adding this kind of beauty is a simple visual technique, the resulting work is not Korean. Or, as Ko Yu-sup wrote, Korean aesthetic beauty comes not from a crafted visual beauty but from an unplanned plan.

Korean aesthetic beauty and its unplanned plan should be seen as an aesthetically original concept that designates the aesthetic particularity of the spirit before being aesthetically original or simple aesthetic originality. These concepts should be seen as a way to create values.

Koreans respect the ability to see. This is their national cultural treasure, and this is what they have developed as the genius of the most Korean art. One way for artists to assimilate this tradition is to make the culture of art include the qualities and values of daily life, thus creating an aesthetic that can be appreciated.

We believe that values are not a given, but are significations discovered and created in daily life. We see with our own eyes the failure of meaningful relationships in daily life. The artist’s culture, will power directed at the world, looks at significations on an invisible level that is imbued with values created by the culture of seeing and that builds the artwork’s world of Korean cultural values.

The painting that our eyes would like to paint is a painting of significations. The signification can become the painting. The signification created is appreciated as a value in daily life. Values are the heart of meaningful relationships in daily life. What is a value? A value is created when the artist paints meaning while looking at meaning. To paint meaning is an act of reason. Will power is born when the heart touches something; and if one appreciates this, then meaning is also born. This is how the literati painter creates meaning.

Our ancestors took pleasure in painting meaning. They neither worried about giving their work a noble or grandiose meaning, nor, for that matter, a meaning at all, nor making a contribution to the world. What they saw was the meaning and quality of a self-contained daily life.

Modernization has made us forget how to use our culture to see the meaning of the world. What our eyes see today is only the world of objects. The eye is only a passage to seeing, and the object worth seeing is created by the desire for a great discourse.

The cultural tradition of seeing is disappearing.

Until now, the eye has failed to use its own culture to paint the meaning of the world, and has existed only as a means of looking at something. Originally, in Korea, the eye has meant a culture of distinguishing and appreciating levels, but not methods and means, of quality.

Our culture of seeing is an aesthetic of the minimal, conceptual judgment of quality in the significations of daily life.

What is important in our art as in our realistic landscape painting is not the natural beauty found in the spectacle of the visible form but the values expressed by the painted world. Aesthetic values address life concepts with the quiet voice of daily life. These values are also apparent in our traditional houses and gardens.

The nature that appears in Korean folk and genre paintings, show little spatial sensitivity because meaning does not come from the relationship between time and space. The development of realistic landscape painting expresses the development of the culture of seeing. The painting’s importance is in how it signifies the value of spectacle. Even more important is how the painting’s culture looks at the spectacular. The development of our ability to see meaning in nothingness is the invisible power of our culture of art. The concept of Korean aesthetic beauty described by art historians until now is nothing more than an expression tacked on to taste.

Unlike today’s Western art tendencies, which are obsessed with art for art’s sake, traditional Korean art has developed as a public cultural practice that expresses values.

Today, techniques for creating something beautiful have advanced dramatically. There are numerous norms of beauty.

Thus, on second thought, techniques of producing beauty are developing beginning with our ability to see values that our ancestors saw. And if the culture of seeing knows how to transform the meaning of the meaning of art into the culture of seeing, then it will avoid becoming a fetish. Art, I believe, can become a culture that paints the beauty of our inner meaning.

Since the nineties, Korean art has recognized once again the tradition of art. Artists no longer ask themselves what the essence of art is, nor how to make art, nor what they can do with art. Art isn’t worried. Since the nineties, artists are hungry for meaning. They are on the front lines in the aesthetic battle for the culture of seeing.

_Translated from Korean by TRANSLATIONS FOR ARTISTS

[1] The semiotic or semiologic concept in question hem is based on the work of Fernand de Saussure and C.S. Peirce in the science of communication.

‘Essentially, the interests of these two areas are similar, and in the end must be assigned to the area called simply communication as a separate general study: Hawkes, T., translated by Chung Byung-hoon, Structuralism and Semiotics (Seoul: Ulyoo Books, no. 256, Ulyoo Moonhwa Co., 1984): p. 173. The use of the icon here also follows the general meaning of Hawkes’s concept, which, in turn, borrows from Peirce’s concept, as in “this means that ‘appropriation’ is suggested in a certain resemblance among signs that are recognized by the receiver.” ibid., T. Hawkes, p.179.

[2] The concepts of Oriental and Western painting are in reality historical. In truth, the real in Oriental and Western concepts is inexistent. The same goes for the concepts of Oriental and Western painting. The concept of Western painting is used here because it is necessary to designate Western art as a contrasting concept with Oriental art since modernization. This means that our ancestors’ paintings are not “Oriental paintings.”

[3] In the dictionary definition of will power” the heart functions to accomplish a work, a desire, or an intention, or a decisive goal toward which one strives. Dictionary of the Korean Language (Seoul: Donga Editions, 1979). In Western thinking the concept of will power appears in such classics as Nietzsche’s Will to Power and Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation. The literati painter’s perception is that of a particular kind of individual who acts through will power to become a public person, even if he or she abandons it or the public rejects him or her.

[4] Simply put, if Western painting represents an object, literati painting represents will power. Since the action painting of the fifties, however, other Western art movements such as color-field painting can be considered representations of will power. Color-field paintings are like literati painting done in a Western style. In their effort, however, to represent the absolute essence of will power, the paintings reveal a different concept from that of literati painting.

[5] Public will power in Asia could be that which is directed at Confucianist human relations.

[6] Oriental painting depends most often on symbolic objects or traditional narratives. Icons are transmitted orally or composed of specific connections among certain scenes and places that hold stories based on historical references, or on animals, plants, and objects that have become meaningful. Icons represent meanings in the rules that govern daily life. The history of Oriental painting is filled with paintings expressing icons that artists have striven to see and appreciate as replicas from orally transmitted history. What the painting represents is a level of quality that the artist saw and took as the intended iconic signification. Icons in Oriental painting symbolize the rules of daily life or an idealized daily life or objects of desire. This interpretation is comparable to a reflection on an absolutely concrete experience of daily life like the ones in the yin and the yang, the five elements -iron, wood, water, fire, earth- the lunar calendar, or color theory.

[7] Of course, North Korea’s Juche(self-reliance) art and South Korea’s Minjung art are similar in their efforts to embrace traditional art forms and to level a severe critique of foreign capitalist and imperialist power. However, Juche art differs from Minjung art in its effort to express the official socialist policy of the North Korean government. Moreover, the South’s interpretation of tradition and artistic language is different from the North’s. The preferred perspective for an artistic language is also different, as is its final destination. Minjung art is part of the world of art. Juche art is part of the North’s revolutionary quotidian.

[8] The history of modernist art in Korea can be divided into before and after the liberation of the country, in 1945. Before the liberation Korean Modernism, which constitutde Korean modern art, was born in the wake of a Western art that primarily came from Europe via Japan. In the period immediately before and after the start of sixties and until the seventies, a Korean Modernism influenced by Amreican art began to unfold.

[9] Although Korean painting can be considered the heir to traditional art, for the past hundred years most works have lost their subjective vision of inheriting tradition correctly, and instead have imitated Japanese painting, or Westernized forms, especially since the nineteen-nineties, when Korean painting and Western painting become indistinguishable.

[10] Yanagi Muneyosi, the Japanese aesthetician, coined the expression “the beauty of sorrow” to describe Korean art. Ko Yu-sup saw in Korean art a craft of non-craft,” or “an unplanned plan: or “simplicity and limpidity.” Until now, the discourse on the originality of Korean aesthetic beauty has been held only among art historians. Yet, in general, their analyses of this originality add little to those of Ko. For more on this subject, see Cho Yo-han, Presentation of Korean Aesthetic Beauty (Seoul: Youl Hwa Dang Publishers, 19991: pp. 27-50.

File Download: The Shadow of Meaning Was Beautiful by Sungweon Kang – with images

© Sungweon Kang